Themes in complaints

Complaints to us often come from students who have additional needs of some kind. This might be that they have a disability or difficult personal circumstances, or because they have other additional challenges affecting their studies, for example international students unfamiliar with the academic expectations of UK higher education.

As well as thinking about what may be helpful for different groups of students such as international students, it's important that providers think about each student as an individual. Complaints often arise when a student feels that their needs are not being met. Listening carefully to the student to understand what they would find helpful and being responsive to their individual needs and circumstances can go a long way towards addressing this. Students are less likely to pursue their complaint if they feel they have been seen and heard by their provider.

Students’ expectations also influence how they feel about their experiences. Clear information for students about what they can expect from their course and from any internal processes they may need to follow, and about what is expected of them, can help to reduce complaints arising.

It is also very important that providers follow a fair process when considering issues. This includes investigating issues properly, considering what evidence is necessary and proportionate, and thinking about what support or adjustments for disability the student or students involved may need.

In this section we explore in more depth complaints relating to academic appeals and complaints from international students, which both rose significantly in 2023. We also look at complaints from disabled students as part of our wider work to promote through sharing learning from our casework.

Complaints relating to academic appeals

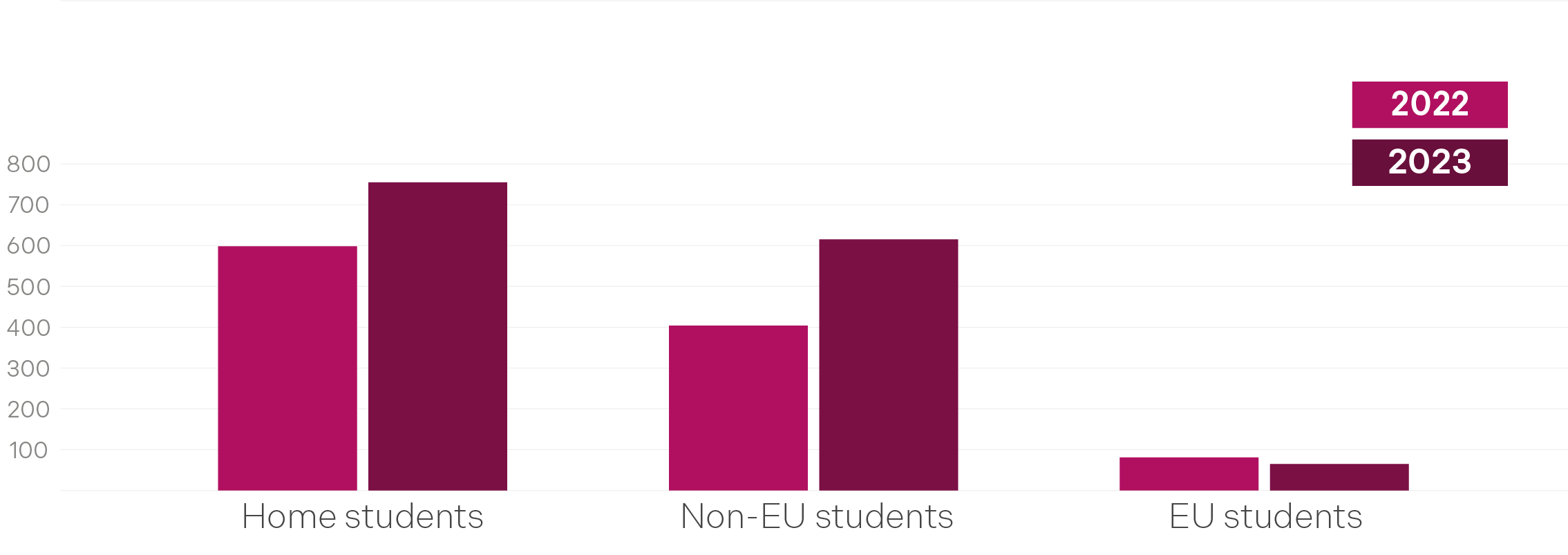

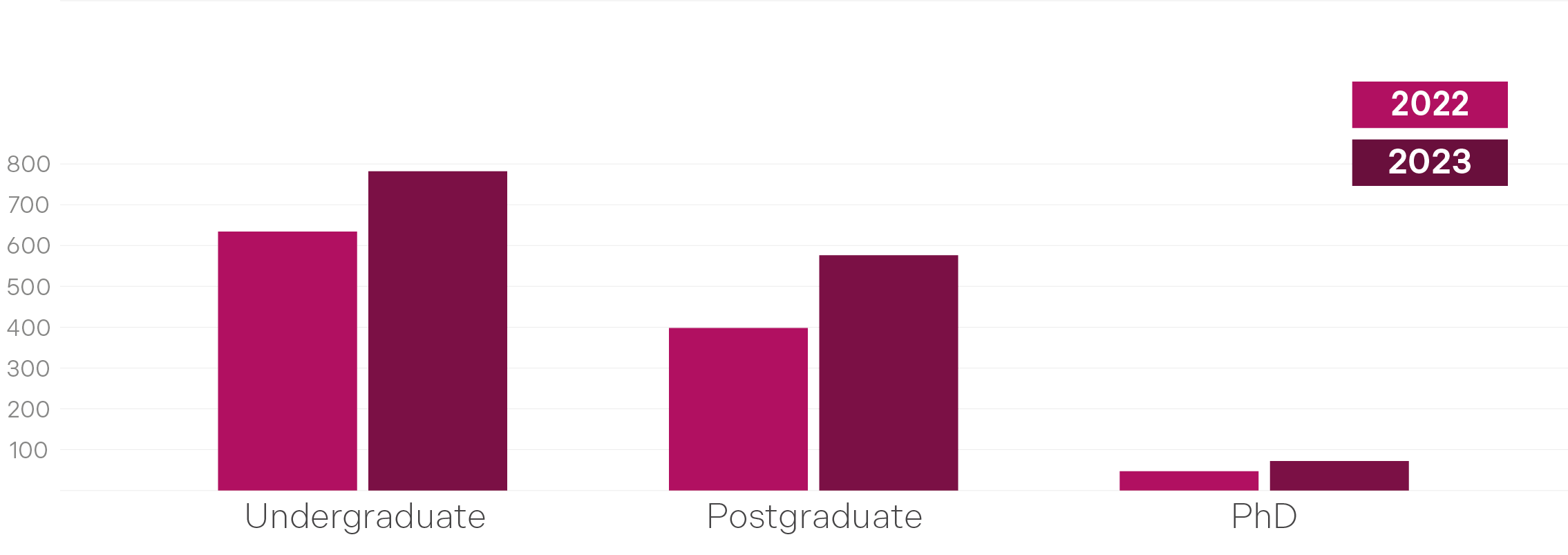

The return to higher levels of complaints relating to academic appeals since the pandemic has been broadly based. Higher numbers of these complaints have come from students at all levels of study, and from both home and international students. However, the rise has been concentrated in complaints from non-EU students and postgraduate students.

Academic appeals by student domicile

Academic appeals by level of study

When we look at complaints relating to academic appeals, we can’t look at matters involving academic judgment. We consider this to be a judgment that is made about a matter where the opinion of an academic expert is essential, not any judgment made by an academic.

Case summary 1

A student made an academic appeal against a fail grade for a practical exam involving interaction with patients in a healthcare setting (an OSCE). The student said that the feedback they received did not match how they remembered the exam at all. For example, the feedback recorded that the student did not wash their hands, but the student was certain that they had done so. The student asked the provider to check that the feedback and mark had not been mixed up with another student’s.

The provider rejected the student’s appeal, saying it was a challenge to the academic judgment of the marker. The student asked for this decision to be reviewed. The person investigating the appeal tried to find the feedback records for the OSCE exam. The module leader had left the provider and the records were not easy to find. The provider rejected the appeal and the student complained to us.

We upheld the complaint (we decided that the complaint was Justified). We did not agree that the student was challenging the academic judgment of the markers. We thought that the provider ought to have done more to establish whether the feedback definitely belonged to this student. We recommended that the provider reconsider the appeal. We also recommended that the provider should review its record-keeping practices so that exam feedback is not lost when there are changes in staff.

As in previous years, in 2023 the majority of complaints relating to academic appeals involved students who were experiencing personal difficulties but did not seek support or use the procedures to request additional consideration of their circumstances at the appropriate time. We also saw complaints where students had unrealistic expectations of what the process could have achieved, for example thinking that their grade could be increased in situations where this was not a possible outcome.

In the complaints we saw, providers were generally handling academic appeal processes in line with the guidance in our Good Practice Framework and this was reflected in the lower uphold rate for this type of complaint. In almost all cases, we were satisfied that information about making a request for additional consideration and seeking support was made available to students. It’s important that providers continue to make this information clear and easy to find and to promote it to students at relevant points in the academic calendar. It’s also important that providers make it very clear what the possible outcomes to a process are so that students can make an informed decision about whether or not to pursue an academic appeal.

Case summary 2

A student passed a foundation year course but did not meet the grade boundary to progress onto a four-year MPharm course. The student was offered an opportunity to enrol onto a different BSc course. The student met with the head of the foundation course and explained that they had suffered a bereavement, and felt that their pastoral needs in the foundation year had not been met. The provider took the issues raised at this meeting forward under its academic appeals and its complaints processes.

The provider rejected the student’s complaint. It decided that all students had been told about a number of ways to access support, and that the student had not made use of the support available. The provider accepted the student’s academic appeal, on the basis that the student had been affected by difficult personal circumstances and there were good reasons for not raising this at an earlier time. The provider offered the student the opportunity to repeat the foundation year as if for the first time, so that they had another chance to meet the entry requirements for the MPharm course.

The student complained to us. They believed that they were very close to the grade boundary and should be allowed to enrol or, alternatively, they should be allowed to just resit some assessments in order to meet the entry requirements.

We did not uphold the student’s complaint (we decided the complaint was Not Justified). The student’s overall mark was not close enough to the grade boundary to be rounded up. Because the MPharm course was regulated by a professional body, the provider did not have any discretion to be flexible in the way the student hoped.

It was clear from the cases we saw that students experience barriers to making use of available processes, even though most knew about them. Some expressed concerns about privacy, and about having to overcome different cultural norms to share personal information. Some described trying to be resilient and push on through. Students who were experiencing mental health difficulties often said that they didn’t fully understand the impact of their mental health on their studies at the time. Some students explained that they did not raise their circumstances because they expected to be advised to defer an assessment and that this would have been so difficult in terms of financial or other practical considerations that they preferred to make an attempt and hope for the best. Some did not feel able for various reasons to obtain documentary evidence to support a request. But most of all, students said that they did not engage with the relevant procedures at the required time because they were overwhelmed by the circumstances they were experiencing at that time.

Some students already have complicated and challenging lives and then find themselves impacted by events such as short-term illness, bereavement, financial crisis or being a victim of crime. It’s reasonable for providers to expect students to engage with processes at the right time but it’s important to balance this with recognising the difficulties this can present for some students and where possible to take steps to reduce the barriers. This can be particularly important where a student is managing ongoing and sometimes fluctuating circumstances. The Good Practice Framework: Requests for additional consideration gives guidance for providers on considerations when personal circumstances are affecting students’ studies.

The accessibility of support services is important. Many providers offer a wide range of supportive services but we commonly see students who did not engage with any formal support mechanism. Students may not always think that their circumstances fit into the areas covered by these services. Students and student representatives have also told us that these services can be extremely busy, and students may not persist if it is difficult to get an appointment.

Case summary 3

A student submitted their assignment online, four minutes after the submission deadline. The work was marked and the student was told the provisional mark was 58%. The provider then lowered the mark to the pass mark because it was a late submission. The student submitted an appeal asking for their personal circumstances to be taken into account. The student described experiencing anxiety and panic attacks following an incident in their student accommodation. The work was due on the first anniversary of the death of a close family member. The student had felt so overwhelmed that they took a short time away from their studies but this meant their work piled up. The student said that they were so anxious that they were unable to articulate their concerns to their tutor, and had not been able to get a medical appointment. They had experienced a panic attack when trying to submit the work.

The provider rejected the student’s appeal because they did not supply any independent evidence about their mental health at the time of the submission.

The student complained to us, and was able to supply new medical evidence. In the light of this evidence, and considering what was proportionate in the circumstances of this case, the provider agreed to remove the penalty it had applied for late submission. The student accepted this offer and the complaint was Settled.

Another area where providers may be able to reduce barriers is in their evidence requirements. In most of the cases we saw, there was no reason to believe that the student was not telling the truth about the circumstances they were experiencing. Some providers had given students examples of circumstances where they were willing to accept that there had been a significant impact on the student without documentary evidence, for example death of a parent, partner, sibling or child. Students with mental health issues often found it particularly difficult to provide supporting evidence of the impact, particularly where they were not able to point to a specific event or incident that caused a change in their wellbeing. It is helpful if providers can be more flexible about deadlines for providing supporting evidence while circumstances are ongoing, and make it clear to students in this kind of situation whether they may exercise any discretion over their evidence requirements.

In our experience students also often don’t understand that if they have not raised their personal circumstances until after the deadline set by the provider, they will usually have to evidence not only the circumstances themselves, but also provide a good reason for not raising them at the time, and support this by further evidence. Many were unable to do this. Sometimes the students hadn’t realised that their reasons for not raising the issues at the time were not sufficiently exceptional for the provider to accept a late submission. It’s important to make the requirements around late requests for additional consideration as clear as possible to students.

Case summary 4

A postgraduate student did not achieve a passing grade for their dissertation at the second attempt. They appealed against the decision to award them a Postgraduate Diploma rather than a Masters award. The student described feeling under pressure before submitting their dissertation and explained that after submitting it a family member had been very unwell.

The student did not make their appeal until eight months after the provider’s deadline. They explained to the provider that they had sought help from an agency and paid them to make an appeal, but they had taken the money and not offered any help. The provider decided that the student did not have a good reason for submitting the appeal late and it did not accept it. The student complained to us.

We did not uphold the complaint (we decided it was Not Justified). We accepted that the student had approached the agency in good faith expecting them to help with the appeal. But the provider had made information available to students about sources of free advice within the provider and via the student’s union, and the student had chosen not to use this help. The student did not have any evidence that showed they were unable to make any contact with the provider during the eight-month period to ask for help.

Academic appeals based on late submission of requests for consideration of additional circumstances create a considerable volume of complaints and administrative burden for providers and are often not beneficial for the students involved. This is a longstanding issue in the sector and we encourage providers to think about what more they may be able to do to address this, from the kinds of approaches outlined above to wider considerations such as course and assessment design.

Complaints from international students

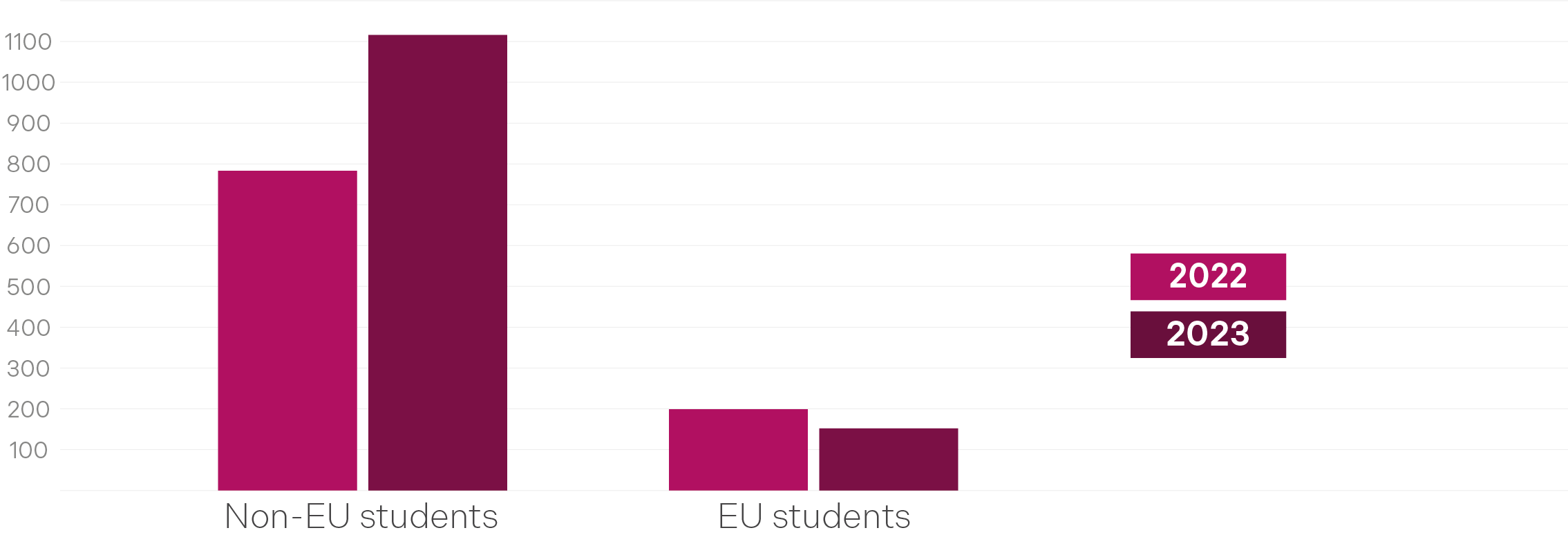

Overall, in 2023 complaints from international students rose to their highest level yet. Within that, the number of complaints from non-EU students (who accounted for nearly 90% of complaints to us from international students) rose by 43% and the number from EU students reduced by 24%, which at least in part reflects the changing numbers of non-EU and EU students in the student population. The sharpest rise in complaints from non-EU students was at postgraduate level.

Number of complaints from international students

International students who have decided to study in the UK often have a clear vision of what they hope to gain from their experience. However, there can be challenges for international students that sometimes mean their experience does not fully live up to their expectations. International students are affected by issues that face students in general, such as cost-of-living and accommodation pressures, and there are also issues that only affect international students or are more likely to affect them, including the political climate and changes in policy direction such as the tightening of visa restrictions, international conflict, public perceptions about their home country, and changes in the relative value of their home currency.

When students find something challenging, they can feel the distance between themselves and their family and home support networks keenly. It can also be difficult for students to cope with news about problems at home when they are unable to return to offer support to family members.

Over half of the complaints from international students related to academic appeals, a higher proportion than for home students. For international students there is often substantial personal and financial investment involved in coming to study in the UK, and sometimes sponsorship arrangements, leading to a possible greater sense of pressure to “succeed” in their studies. It can also be more difficult for international students to make use of options such as taking time out from their studies if they are experiencing difficulties, and some options may not be available to them due to visa requirements.

Case summary 5

After two assessment opportunities, an international student was successful in some modules but unsuccessful in others. The provider decided that the student could not progress onto the next year of the course until they had passed the outstanding assessments. The student was allowed to re-take the assessments in the next academic year without attending the teaching again. This meant that the student would need to leave the UK until the assessment period, because their visa was only valid while they were attending classes on a full-time basis.

The student submitted an academic appeal based on personal circumstances which had affected their mental wellbeing during their studies. The student asked to be allowed to attend teaching for the outstanding modules on a part-time basis because they felt that a repeat of the teaching would be helpful to them, and explained that because their family had relocated they did not have a family home to return to.

The provider rejected the student’s appeal. It noted that the information about the student’s personal circumstances should have been submitted earlier. But even if it had been, the provider couldn’t offer what the student wanted, as it was not allowed to sponsor any international students on a part-time basis. Even if the student’s claim for mitigation had been upheld, the outcome would have been to allow the student a further opportunity to take the outstanding assessments, which had already been allowed.

The student complained to us. They supplied new medical evidence about their mental health during their studies and suggested that their mental health difficulties might amount to a disability. Our review focused on the matters which the student had raised with the provider in their appeal. We decided not to uphold the complaint (we decided it was Not Justified). We were sympathetic to the student’s difficult circumstances, but it was not open to the provider to offer the student an opportunity to stay in the UK and study on a part-time basis.

The issues raised in academic appeal complaints from international students were quite similar to those from home students, mainly around requests for additional consideration due to personal circumstances including late submission of requests. In some cases students mentioned concerns about the quality of teaching or supervision in their academic appeal to the provider even though they had not raised these issues with the provider or made a complaint about them while their course was ongoing.

Understanding and adapting to academic expectations in UK higher education can be difficult for international students, especially for those whose previous academic experience is very different. It’s important that providers do all they can to help international students to understand what is expected and what is and is not considered acceptable academic practice. International students were disproportionately represented in the complaints brought to us at the end of academic misconduct procedures, and the proportion with a favourable outcome (Justified, Partly Justified or Settled) was lower than for home students.

We also saw some cases where the student’s English language level had made it difficult for them to understand expectations and processes and more widely to fully benefit from their studies. Using clear, simple language in guidance and procedures and avoiding unnecessary jargon and legal terms benefits all students but can be particularly important for students whose first language is not English.

Case summary 6

An international student was called to an academic misconduct meeting because their answers to a closed book exam had included a significant proportion of text copied from published sources and lecture notes. The student had not cited the source of the text in their answers.

The student explained that their practice was to memorise large portions of text and present these in exams, and that this approach had earned them high marks in the past.

The provider concluded that the student’s method had been deliberate but that they had not understood that this approach could appear to present the work of others as the student’s own and that this was a type of academic misconduct. It decided that this was a case of poor academic practice. It imposed a mark of zero for the exam and allowed the student to attempt the exam again, for a capped mark.

The student complained to us because they did not feel it was fair to have a disciplinary concern on their record. We acknowledged that the student had been acting in a way that was familiar to them from their previous educational experiences. We decided not to uphold the student’s complaint (we decided it was Not Justified). The provider had made it clear to all students that answers given in closed book exams should be in the students’ own words. The provider had taken account of the student’s explanation in imposing the lowest penalty available under its procedures.

Various other issues were raised in complaints from international students. These included termination of studies due to a lack of attendance or engagement, most commonly in the context of visa requirements, and small numbers relating to significant changes in the value of some currencies and to the practices of some agents used to recruit international students.

"Thank you for your review of my case… I appreciate the clearly comprehensive review that you have undertaken.”

Case summary 7

An international student studying in the UK on a Student Visa received a letter from the provider telling them that their studies had been terminated because their attendance was 0%. The student appealed against this decision. They described a series of problems at the beginning of the academic year in getting their student card to work and in receiving correct timetable information. The student said that they had spoken to a student helpdesk to resolve the issues. They had attended all their classes, had submitted all of the required work and had achieved good marks so far.

The provider rejected the student’s appeal, saying it was not satisfied that the student had provided evidence that there had been problems with their student card and registration. The provider said that the student should have asked individual academic staff to record their attendance in classes. It asked some of the academic staff if they could recall the student being present, but academic staff were not able to confirm this.

The student complained to us. We upheld the complaint (we decided it was Justified). The provider had not looked for any information about the student’s card and whether there was a record of the student seeking advice from its helpdesk. The provider could not show that the student had been advised to ensure that academic staff made an additional record of their attendance. The academic staff who had been asked about the student’s attendance had noted that much of the delivery was in lectures with a very large number of students in attendance and they could not recall individual attendance accurately.

We recommended that the provider should consider the student’s appeal afresh, having gathered more relevant information about the accuracy of its records of attendance for this student.

"Thank you very much to the team at OIA for investigating my complaint thoroughly. After reading the outcome report, I agree with the OIA’s findings and I believe all of their comments to be fair and accurate…. I would like to... also thank [the provider] for deciding to address my complaint when they were under no obligation to do so.”

Complaints from disabled students

A third of students who complained to us in 2023 identified themselves as disabled. This is self-reported, so it is possible that some of these students’ conditions may not meet the definition in the Equality Act 2010, but it is also likely that some students chose not to tell us about their disability. While numbers are not exact, disabled students continue to be significantly overrepresented in complaints to us (as an indicative comparison, disabled students made up 16% of the student population in England and Wales as reported in HESA statistics for 2021/22, although this may be somewhat higher now as numbers of students known to be disabled have been rising). The proportion of students who complain to us who have disclosed a disability has also been steadily rising over the last few years.

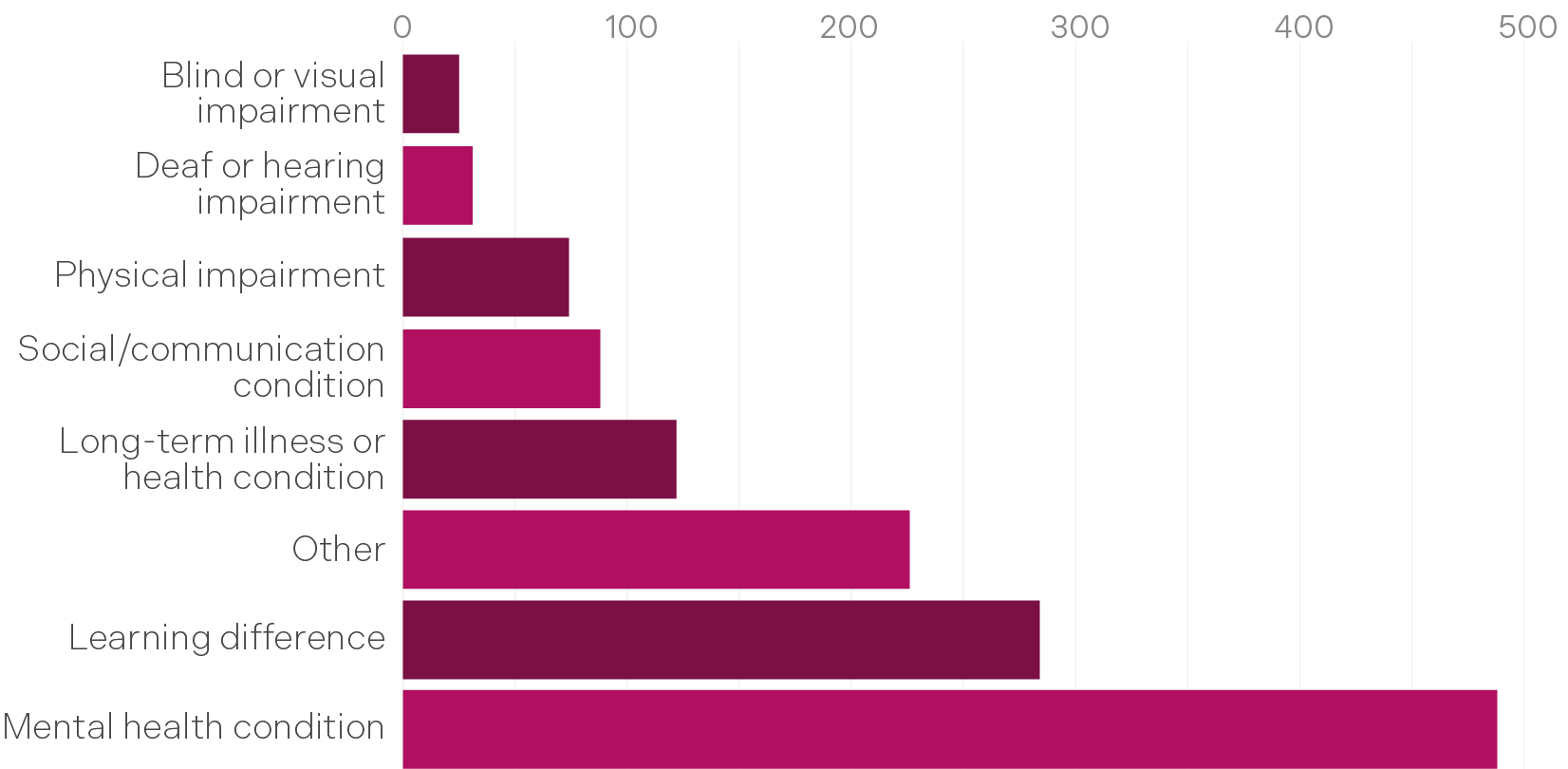

Prevalence of different types of disability

Of students who identified themselves as disabled, around 45% reported a mental health condition, and the actual proportion is likely to be higher as some of those who selected “Other” described experiencing mental health difficulties. Around a quarter indicated that they had a specific learning difference. A large majority reported that they had more than one disability (students can select all that apply). Many students selected “Other”, possibly suggesting that they didn’t relate to the available options and in some cases that they preferred not to specify their disability.

Breakdown of reported disability types

Of complaints received where a disability was reported

While there are some differences between the prevalence of different types of disability in currently available sector-wide data and in complaints to us, the increasing number of students reporting mental health conditions is a consistent theme. We see in our casework the impact that poor mental health can have on a student’s ability to engage effectively with their studies and with providers’ internal processes. It is very important that students who are experiencing mental health issues are supported. During the year we contributed to wider work on this issue.

What disabled students complain about

In 2023 there were some small differences in the category of complaints from students who have disclosed a disability to us, in comparison to those students who have not. The proportion of academic appeals was slightly lower, and as might be expected there were a higher proportion of complaints categorised as equality/human rights and welfare/non-course service issues.

There are broadly three types of complaint we receive from disabled students. Many of the complaints to us in 2023 were either unrelated to the student’s disability (for example how their domicile has been categorised for tuition fee purposes) or about issues that can affect any student but had a greater impact on the individual student because of their disability. We also received a smaller number of complaints about issues that can only affect disabled students, such as concerns about reasonable adjustments.

It can be challenging for providers, especially in the context of a large number of students, to recognise and meet the needs of individual students. It’s very important that providers think carefully about disabled students in their planning, including when making changes to course provision, and listen to and address the needs of individual disabled students.

Course changes can sometimes present particular difficulties for disabled students. While all students benefit from clear and timely communications about their studies, students affected by anxiety or who have conditions affecting how they process and respond to unexpected circumstances can be more significantly affected where communication is late or unclear. A change such as how a module is delivered can also create practical difficulties for some disabled students.

Case summary 8

A student affected by generalised anxiety disorder was part of a cohort affected by industrial action. The provider proactively considered whether any teaching had not been delivered, and offered students on this course compensation of £250. The provider had set up a special process for students to make further submissions about the impact that the industrial action had had on them individually. The student made a submission and the provider increased its offer to the student to £500.

The student was dissatisfied and complained to us. They described the impact of the industrial action as very severe, because of their pre-existing anxiety. The student described how this worsened because they were unable to talk to tutors about their studies at various points of industrial action. The student had felt that they needed to suspend their studies. The student provided medical evidence that described how they had been feeling in recent months.

The provider contacted us. It said that in light of the more detailed statement the student had made in their complaint to us, it would like to offer more compensation. The student accepted the offer of £2,200 and the complaint was Settled.

Some of the complaints we saw showed the difficulties disabled students can experience studying within a system that is primarily designed around full-time study within defined academic years. In a number of cases, providers had tried to enable students to take a flexible route through a course of study by allowing time away, extending the time allowed to complete work, or allowing a student to flex between full-time and part-time attendance. However, students were not always clear how these options may affect their eligibility for financial support or be compatible with visa requirements. Sometimes the student couldn’t take advantage of the flexibility that was offered because of these practical issues. Similarly it can be more difficult for some disabled students to engage effectively with the expectations of structured processes and timeframes.

In 2023 we continued to receive complaints from disabled students about how they were or were not supported to access their studies. For example, we saw complaints about how reasonable adjustments were agreed and communicated to academic staff and staff in placement settings, and complaints from students about particular academic staff being reluctant to change their practices to be more inclusive.

Case summary 9

A student with an autistic spectrum condition and a physical disability was studying a course in the performing arts at one provider (provider A) leading to the award of another provider (provider B). During their second year, the student raised concerns with provider A about a lack of support and said they were unsure if they could continue on the course. After informal discussions did not resolve their concerns, the student made a formal complaint to provider A. Provider A acknowledged some serious shortcomings in its communication with the student due to staff changes, but rejected the complaint overall. It referred the student to provider B’s Complaints Policy. Provider B told the student that it did not have any remit to review the complaint because it was not about the quality and academic standards of the course. The student then received a Completion of Procedures Letter from provider A and complained to us.

We upheld the student’s complaint (we decided it was Justified). There had been a failure to explore what the student’s specific needs were in the context of the course, and to identify and put in place support or reasonable adjustments. There had been confusion about whether students should seek this support from provider A or provider B, and about what kinds of complaints could be referred to provider B. Provider A had acknowledged some significant areas for improvement and had taken steps to improve some policies and to deliver staff training. In spite of this, it had rejected the complaint in full and missed an opportunity to put things right for the individual student. The student had lost faith in the provider and withdrew from the course.

We recommended that provider A should apologise to the student and pay them compensation of £5,000. We also made Recommendations to provider A about the operation of its complaints procedures drawing on the guidance in our Good Practice Framework.

In some cases, students raised issues within their complaint to us about how they had been supported to use internal processes at the provider. For example, some students with social communication difficulties said that meetings had felt hostile and that decision-makers had misinterpreted their intentions, even though the provider had made what it considered to be appropriate adjustments to enable the student to participate fully. It is helpful if providers engage in an open way with individual students to find out what they feel will be most helpful, and are clear about what adjustments they are offering.

During the year we heard from our Disability Experts Panel about difficulties that some students had faced in obtaining evidence for claiming Disabled Students’ Allowance, in getting a needs assessment, and in finding suitably skilled people to provide recommended support, in particular a shortage of British Sign Language interpreters. However, we did not see this reflected in many complaints. It is likely that some students are being supported by providers to overcome these obstacles, but it is also possible that some disabled students are not raising these issues through complaints processes. We heard from the Panel that it is hard for some disabled students to find the time and energy to make a complaint, due to both their disability itself and the need to engage with other processes or arrangements because of their disability.

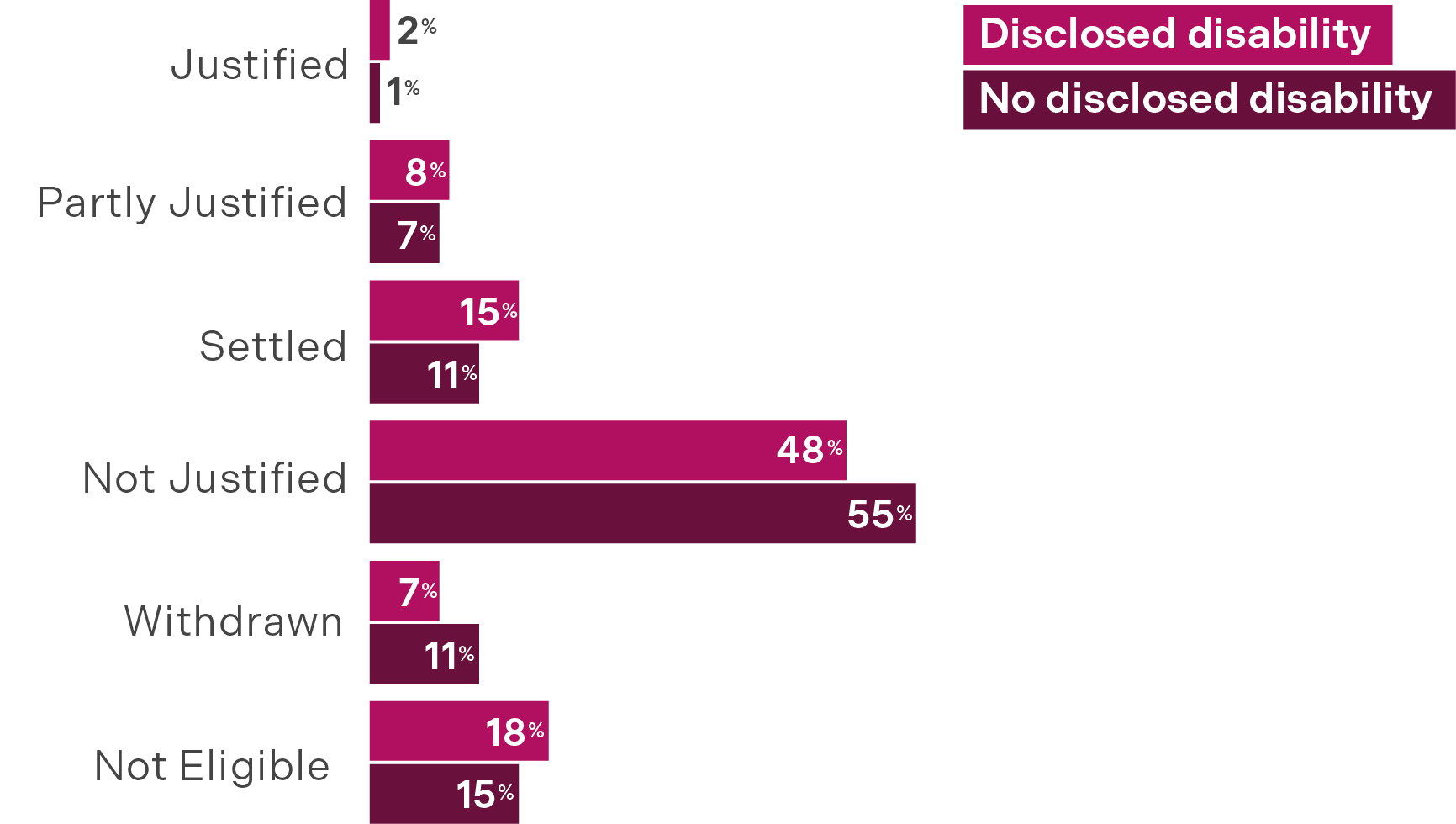

There were also some differences in the outcomes to complaints between students who disclosed a disability, and those who did not. A higher proportion of disabled students received favourable outcomes to their complaints in 2023. In particular, more complaints were settled, sometimes where additional information in the student’s complaint to us led to providers being willing to consider students’ circumstances afresh.

Outcomes by disclosed disability / no disclosed disability

“Thank you for your email, and taking the time to get back to me. Your answers were very clear, so I wanted to express an additional thank you for responding within my reasonable adjustments request.”

Other observations from our casework

In 2023 although the number of complaints we received from home students overall was broadly stable, there was a small reduction in complaints from home undergraduate students. This was most notable in the number of complaints relating to service issues, which had been higher in recent years primarily due to complaints relating to the pandemic and to a lesser extent industrial action.

The marking and assessment boycott that affected some providers did not result in a large number of complaints to us. This may be at least in part because providers have become more experienced at minimising the impact of disruption on students, and at assessing and taking appropriate steps to remedy any negative effects on individual students. We hope that our guidance on handling complaints arising from significant disruption has been helpful.

Sexual misconduct and harassment continues to be an important concern. The number of complaints we receive relating to these issues has risen slightly in recent years but remains small. We have seen more instances where students whose complaint is mainly about a different issue mention experiences such as harassment or domestic violence as part of the context of their complaint, perhaps reflecting a greater confidence in talking openly about these experiences. In 2023 we also continued to receive complaints from students who had been accused of sexual misconduct. These complaints were often centred on the fairness of the disciplinary process. There is a difficult but important balance for providers in trying to handle concerns about these issues sensitively and in a way that minimises distress for the reporting student whilst making sure that processes are fair for all involved. During the year we engaged with relevant developments, learning from work such as Higher Education After #MeToo: Institutional responses to reports of gender-based violence and harassment. We also shared learning from complaints to promote good practice, including publishing a casework note on complaints relating to disciplinary matters and contributing to sector discussions and events on these issues.