Themes in complaints

In this section we explore in more depth complaints from students at the end of an academic appeals process, complaints from disabled students and complaints about bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct.

Academic Appeals

In our reporting, the category of “Academic Appeals” includes complaints students have brought to us at the end of various processes that make decisions about a student’s progression on their course of study, and about their assessments. Most academic appeals cases are brought to us by students who feel their performance in particular assessments has been affected by circumstances beyond their control, and who are unhappy about how their provider has taken their circumstances into account. We also receive complaints about procedural irregularities in how an assessment was run, and a small number that allege bias in the assessment process. Complaints about bias are more common in assessments that cannot be submitted anonymously, for example postgraduate research vivas or assessment of practical skills on placements.

It is relatively unusual for students to complain to us about the specific marks awarded for a single assessment. Many of the academic appeals decisions we review are about whether a student is permitted to continue with their studies at all. For undergraduates this usually relates to achieving too few credits before the start of the next academic year. Postgraduate research students’ complaints often concern decisions about whether they have made sufficient progress in the early stages of their research.

The “Academic Appeals” category also includes complaints from students who have not been allowed to continue with their studies because they have not met the requirements of their provider’s attendance or engagement regulations. Providers often take a firm line on attendance requirements, reflecting both their responsibilities as a visa sponsor to monitor the attendance of international students, and the view that regular attendance and engagement gives all students the best opportunity to succeed in and benefit from their studies. It is important that providers have reliable mechanisms to monitor attendance accurately. Students also benefit from early warnings if their attendance is not at the level expected, and clear opportunities to discuss any welfare issues that may be relevant.

We don’t uphold most complaints relating to academic appeals. We rarely see examples of academic appeals processes that are incompatible with the Good Practice Framework, and we usually conclude that the provider has followed a fair process. Students’ complaints to us about academic appeals don’t always try to establish that a provider has not acted in accordance with its own regulations. In many cases the student is simply expressing the hope that a provider might be persuaded to reach a different decision.

Students make a significant personal and financial investment in pursuing higher education studies, and many tell us about the immense pressure they feel to succeed. For some of these students, knowing that they have taken every opportunity to make their case and having the reassurance of an independent perspective will help them move forward on an alternative plan.

We know that some providers are addressing increasing numbers of academic appeals, and that using templates for correspondence can help provide the necessary information to large volumes of students in a timely way. In our experience, students benefit from correspondence that goes beyond providing a series of results codes and a link to the relevant provider regulations. Students prefer clear explanations about what this means for them, and value acknowledgement where they have experienced particularly difficult circumstances. Some students who might otherwise have accepted an outcome from their provider are motivated to complain to us by a perceived lack of humanity and compassion in the provider’s response. Similarly, students complain to us where inaccuracies in the provider’s correspondence undermine their confidence that their circumstances have been carefully considered.

A student nurse had several periods of interruption to their studies because of ill-health, non-payment of their tuition fees, and delays in obtaining an up-to-date DBS certificate. When the student returned to their studies, they expected to complete approximately 400 placement hours. At a return-to-study meeting, the provider told the student that they needed to complete a further 1,300 placement hours. The student disagreed with this, and the provider considered their objections using its academic appeals procedure.

The provider said that the rules around placement hours are set by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (the NMC). The NMC rules say that if a student takes a long time away from their studies, some earlier placement hours cannot be carried forward. At the end of its review the provider said again that the student needed to complete another 1,300 hours because they had been away from their studies for two years.

The student remained dissatisfied and complained to us.

We upheld part of the student’s complaint (we decided it was Partly Justified). The provider had correctly applied the NMC rules, and the student was required to complete a further 1,300 placement hours. The provider was not able to change these requirements.

But the provider had not clearly explained to students how any periods of absence might affect the requirements around placement hours. The return-to-study meeting had not given the student enough information to understand the requirements. After that meeting, the provider had asked the student to write an email summarising what they had understood which the provider would then amend. This was not good practice. It was the provider’s responsibility to provide a clear note of the meeting, outlining exactly what the student needed to do to complete their qualification. The provider had also undermined the student’s faith in the fairness of the process by repeated inaccuracies when describing how long the student’s time away from study had been for different reasons.

We recommended that the provider should apologise to the student for the distress caused by a lack of clarity in its communications and pay £500 in compensation. We also suggested that the provider should add more information to the programme handbook about circumstances when some placement hours might be discounted.

Some of the complaints we review give us insights into the challenges students face in balancing their studies with their other commitments. Students who are time-poor may find it difficult to seek out help until it is too late.

A student studying for a Postgraduate Diploma via distance learning was withdrawn after they were unsuccessful in a module for the second time. The student appealed on the basis that they had been disadvantaged when the provider changed their virtual learning environment (VLE) platform. The student included screenshots of the new VLE system that showed failed login attempts, and screenshots from WhatsApp conversations with other students about problems with the new VLE.

The provider invited the student to an appeal hearing to hear more about how they used the VLE. The student said that they accessed it on their phone because they only had time to study when commuting to their paid employment or when walking in the evenings. The student confirmed that they had not asked for any help to access the new VLE.

The provider looked at the access logs to the VLE. This showed that the student only had failed login attempts when they had entered the wrong password and there were no other problems with the student’s account. The student’s pattern of accessing the VLE was similar for the old and new systems. The provider noted that students were advised not to try to complete their studies only using a mobile phone.

The provider rejected the student’s appeal, and the student complained to us. The student suggested that the provider shouldn’t have looked at the access logs but should only have considered the screenshots they had supplied.

We did not uphold the student’s complaint (we decided it was Not Justified). It was reasonable for the provider to look at the information it had about VLE access to see if anything was wrong with the way the student’s account had been working. It was also reasonable to expect that the student should have asked for help at the time they were experiencing any difficulties with the VLE.

“Because of your dedicated efforts, I have been given the opportunity to resubmit my dissertation. This opportunity is incredibly meaningful to me, and I am profoundly grateful for the pivotal role you played in making this possible.”

Some of the complaints we see illustrate how students who have been experiencing difficulties may make poor choices about how to continue with their studies.

An international student was unsuccessful in three modules and was required to re-submit assessments. The student made an academic appeal asking to be allowed to re-submit work for a fourth module, in which they had received a low pass mark. The student supplied a letter describing mental health issues they had been experiencing. The letter appeared to be from a local NHS Trust.

The provider’s regulations set out that it would take steps to verify evidence supplied with academic appeals. The NHS Trust confirmed that it had not issued the letter and that it appeared to be a forgery. The provider paused the academic appeals process and considered the issue of the forged letter under its academic misconduct processes. The student said that the letter was not forged but blamed errors in translating and transcribing documents from the language they were originally written in. The provider was not persuaded by this explanation. As a result of these processes, the student’s studies were terminated. The student did not complain about this decision to us.

The provider then confirmed to the student that it would not be proceeding with the academic appeal. The student complained to us about this decision. The student wanted to supply new evidence in support of their academic appeal.

We decided the complaint was Not Justified. Since the initial evidence supplied by the student was not genuine, their submission had not clearly established any grounds for the provider to consider their appeal. The student had not given any good reason as to why they had not been able to supply genuine evidence at the correct time. We explained to the student that even if the decision about the module the student had passed was different, this would not have altered the fact that the student’s studies had been terminated for misconduct.

Complaints from disabled students

In our 2023 Annual Report we highlighted that disabled students were over-represented in complaints to us, making up around one-third of our caseload. In 2024, the proportion of complaints brought to us by students who tell us they are disabled has risen again, to just over 40%. It is possible that some of these students’ conditions may not meet the definition of a disability under the Equality Act 2010, for example because the condition is likely to be of a short duration. Some other students may be disabled but choose not to tell us. While this means we can’t be exact about the number of complaints we have received from disabled students using the legal definition, a significant number of students feel it is relevant to mention their health and wellbeing in the context of their complaint.

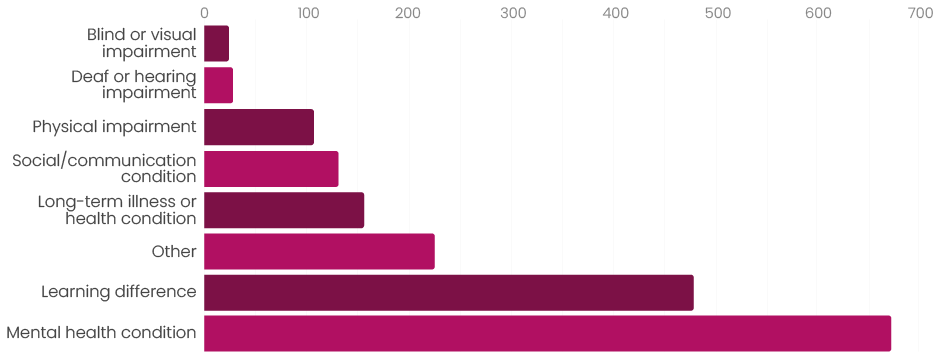

Some students choose not to disclose details of their disability or health condition. Of those who did describe their disability, the largest category selected by students was “mental health issues” (46% of the total who provided details). This continues the trend we have seen in recent years and is consistent with sector-wide data. Specific learning differences accounted for 33%. Just under 40% indicated that they are affected by more than one condition. Neurodivergent students described their condition using a variety of options, which may reflect a variety of different routes to diagnosis.

Breakdown of reported disability types

What disabled students complain about

We have reviewed complaints from disabled students and the distribution of complaints within the categories we use is very similar for disabled and non-disabled students.

Not every complaint from a student who identifies themselves to us as disabled begins with an experience directly connected to their disability. But in our experience, the complaints that are prompted by events that have only taken place because the student is disabled are likely to have had a significant and lasting impact.

We continue to receive complaints from students about the implementation of support and reasonable adjustments to teaching and assessment. In some cases, it has taken a long time to identify what support will work best for the student for their course of study. This can be because of significant delays in the process once a student has applied for the Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA). In other cases, academic staff have not fully understood what is required and default to standard practices that don’t meet disabled students’ needs. It is important that providers train and support academic staff in meeting the requirements of the Equality Act 2010. 15 years after its implementation, we still see instances where there is no clarity for students or staff within course documents about what competence standards will be assessed. We welcomed the advice note published by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in July 2024 which explores what compliance may look like.

It is not our role to make findings about the actions of individual members of staff working at providers. But we are concerned that in some instances, there is no culture of accountability in place to ensure that disabled students receive the support that is necessary to place them on an equal footing for success with their peers. We are also concerned about the resourcing of support for disabled students in the context of wider financial pressure and delays in the DSA system.

A partially sighted student enrolled on a one-year taught Masters course. Students could access their core texts and additional reading using an online database. In October, the student told the provider that they were having some difficulty using the online database. In January, the student explained that their assistive software could not read the text at all. The provider contacted the database supplier to try to find a solution. The provider also supplied the student with digital copies that were accessible and printed versions of texts when the student asked for them.

At the end of the year, the student complained that the provider had not made reasonable adjustments effectively or quickly enough, and that this had affected their academic performance and overall experience. The provider rejected the student’s complaint, saying that it had responded promptly and provided alternative versions of the texts for the module that was affected. The student remained dissatisfied and complained to us.

We upheld the complaint in part (we decided it was Partly Justified). Unfortunately, the student had not made clear the extent of the problem with the database and the assistive software when they first mentioned experiencing difficulties. Once the provider understood the impact of the problem, it had acted promptly and tried hard to find a long-term technical solution. But we thought it was not reasonable for the provider to conclude that only one module had been affected. The provider had access to the reading list for the course which showed that access to many texts in the database was required across all the modules. The provider could have provided these in an alternative format proactively rather than waiting for the student to request them one by one.

The student did not want to engage in any further study opportunity at the provider. We recommended that the provider apologise and offer compensation of £2,500 for the distress and inconvenience caused by the failings we had identified.

“Before the OIA’s independent recommendation I did not have a real voice in the matter as I was only given forms and deadlines which I personally find very challenging to navigate. The independent recommendation of the OIA allowed me to speak [...] directly via a hearing where as a disabled person I was able to better communicate the truth of the situation. Consequently, I have a real chance at completing my studies and continuing my career.”

A disabled student complained to their provider that the reasonable adjustments they needed to support them in their studies had not been put in place for most of the academic year. They complained that this amounted to discrimination and was a form of bullying and victimisation. The student also complained about support in arranging a placement.

The provider investigated the complaint. It concluded that staff had been willing to support the student but there had been a lack of information about some of the student’s requirements and that this had contributed to the adjustments not being made. It partly upheld the complaint, apologised and offered the student £100 compensation. It also said it would take steps to put the reasonable adjustments in place going forward. The student was dissatisfied and complained to us.

We upheld some parts of the student’s complaint (we decided it was Partly Justified). We decided that the provider’s conclusion, that staff had been willing to make adjustments but that there had been a lack of information about what was required, was not supported by the evidence. It was clear that some academic staff had refused to make adjustments that had already been agreed in the student’s support plan. The provider was wrong to conclude that the student’s requests had changed.

We were also critical of the provider because it had not addressed the student’s claim that they had been bullied.

We were satisfied that the provider had acted reasonably in providing the student with support to arrange a placement.

We recommended that the provider should apologise for the failings we had identified and pay the student £5,000 in compensation, recognising the significant impact that the lack of adjustments had received. We also recommended that it apologise and offer to begin a new investigation into the student’s complaint about bullying.

A student had a long-term health condition which caused pain and mobility issues, and which was subject to flare ups. Before enrolling on the course, the student was told that they could access teaching remotely during flare ups. Shortly after the student enrolled on the course, they had a flare up of their ongoing condition. After one month staff raised concerns with the student about their attendance. Staff said that remote attendance was not permitted because of the requirements of a professional regulatory body. The student withdrew from the course before the end of the first term.

The student made a complaint about their experience saying that the provider had failed to make reasonable adjustments for them as a disabled student. The provider rejected the complaint, describing the student’s claims as “false” and writing that the student was “feeling entitled” based on “poor understanding”. The student complained to us.

We upheld the complaint (we decided that it was Justified). The course was not directly accredited or regulated by the professional body, although graduates might choose to register with it. The information provided to students about this was unclear. It was incorrect for the provider to say that the requirements of the professional body prevented it from considering making a reasonable adjustment to its in-person attendance requirement. We were also critical of the tone of the provider’s communications with the student.

We recommended that the provider apologise to the student and pay £2,500 compensation for the distress and inconvenience caused by its failure to properly consider its obligations under the Equality Act 2010, and that it should cancel the student’s tuition fees. We also recommended that the provider should review its procedures and practise to ensure that there is a formal mechanism for deciding what adjustments can be put in place to support disabled students and to ensure that these decisions are documented.

“Thank you for dealing with my complaint so efficiently and for keeping me informed each step of the way. Whilst it was not entirely the outcome I desired, I have somewhat had my faith restored in a complaints process. I have also been impressed with the accommodations available for those who are neurodivergent. I especially found the decision outcome to be clearly written and structured.”

In some cases, disabled students do not raise any concerns about how they have been supported until after receiving their results when they make an academic appeal. In general, we have seen providers directing students towards support services when students share information about the difficulties they are experiencing, and these services are also usually well-publicised on providers’ websites. In our experience, students facing challenges with their mental health may not take up this support, either because they do not realise how much they are struggling, or because it seems too overwhelming to do so. For some students, there is still some stigma attached to seeking help.

A student on a one-year postgraduate taught course was living with depression which affected their ability to meet some coursework deadlines. The provider agreed several extensions to deadlines. 14 months after beginning the course, the student had one piece of coursework outstanding, which they were attempting for the second time. On the submission date the student asked for their circumstances to be considered because they were not able to submit the work in full. The provider responded by email on the same day saying that the request was refused. The student submitted their unfinished essay. Three weeks later, the provider told the student that they had not passed the module, and that their studies would be terminated.

After three weeks the student made an academic appeal. The provider responded the next day accepting the appeal and saying it had made a mistake when rejecting the student’s earlier request. It confirmed that the student could continue their studies and have a further attempt at the outstanding coursework.

The student made a complaint about how the mistake had affected them. The provider again accepted that it had made a mistake. It apologised to the student and offered them £500 compensation in recognition of the distress this had caused.

The student remained dissatisfied and complained to us. The student explained that the error had caused them very serious distress and that they had been suicidal for several months afterwards. They said that they had lost a job offer because they had not been able to complete the course and obtain the required professional registration in time to accept it. The student requested £20,000 in compensation.

We did not uphold the complaint (we decided it was Not Justified) because we thought that the provider had already offered the student a reasonable remedy that was proportionate to the mistake it had made. It had acted quickly to tell the student they could continue with the course. The mistake had not delayed the student in achieving their professional registration; unfortunately, because the student wasn’t able to meet the original deadline it would never have been possible for the student to achieve professional registration in the timeframe required to take up the job.

In recent years we have seen several changes to providers’ approaches that have benefitted disabled students. For example, we have seen fewer examples of disabled students needing to repeatedly supply medical evidence about the same condition. Many providers have introduced policies that allow all students to self-certify for short periods of ill-health that affects attendance or assessments, and that are like policies commonly used for employees. We have also seen improvements to practices in communicating a student’s support needs when they have been agreed.

It is important to remember that disabled students’ conditions affect their daily lives and student experience in the round. Providers must be alert to students who may need additional support engaging with a range of formal processes and respond to students as individuals.

An apprentice enrolled on a degree apprenticeship in a regulated profession needed to successfully complete a maths functional skills qualification before they could progress to the end point assessment. The apprentice complained that there had been a lack of support for them as a person with dyslexia and ADHD and asked that the level of the qualification be lowered as a reasonable adjustment. The provider initially rejected the complaint. Under the “Apprenticeship Funding Rules for main providers” set by the government, higher education providers are permitted to lower the maths functional skills requirements for apprentices who have an Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan, a statement of special educational need (SEN) or a Learning Difficulty Assessment (LDA). The apprentice did not have any of these documents.

The apprentice asked for the decision to be reviewed. The apprentice had undertaken initial screening earlier in their studies and had then been evaluated by a psychologist that was on a list of approved needs assessors supplied by the provider.

The provider decided to accept the psychological assessment, in the light of very long waiting times for further assessment to obtain more formal documentation. It reduced the level of maths functional skills qualification that the apprentice would need to achieve. It also offered the apprentice £1,000 in compensation, recognising that the delivery of maths support tuition had been disrupted.

The apprentice was dissatisfied and complained to us. The provider made a revised offer of £5,000 to settle the complaint. The apprentice rejected this offer. They argued that the issues had caused delays in completing their qualification, and that because of this they had lost out on an increased salary.

We did not uphold the complaint (we decided it was Not Justified) on the basis that the offer the provider had made was a reasonable remedy for the complaint. The apprentice’s claim for lost earnings was speculative; it was not possible to say that if the provider had acted differently, they would have successfully passed the end-point-assessment at an earlier date.

Complaints about bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct

In 2024 we continued to see an upward trend in the number of complaints we received that contained some element of bullying, harassment or sexual misconduct, although overall numbers remain below 5% of our total caseload.

In some cases, these kinds of behaviours are not the focus of the complaint. For example, in a small number of cases, we have reviewed a provider’s response to an academic appeal which included disclosures from students about their mental health, connected to their experiences of domestic abuse or sexual assault perpetrated by individuals outside the provider’s community. We think the reason that we may be seeing more of these examples is because students are feeling more confident in sharing these experiences with their provider.

We have reviewed complaints from students who have reported the behaviour of others, and from students whose own behaviour has been the subject of a complaint. Most of the complaints we reviewed in 2024 at the end of a non-academic disciplinary process were from reported students about their behaviour towards others, with a smaller proportion relating to more general misbehaviour (for example theft, drug use or failure to respond to fire alarms). A larger proportion of these disciplinary complaints related to sexual harassment, gender-based harassment or misogyny than to any other protected characteristic and most reported students were male.

Most students who brought a complaint to us about the behaviour of others were female. The majority were complaining about the behaviour of other students, although some complaints involved the actions of members of staff. It is the nature of our Scheme that students who are satisfied with how a provider has responded to a report about bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct would not approach us. The students who did complain were dissatisfied with a range of issues. One area which has proved very challenging for providers is managing a disciplinary process for the reported party with an appropriate degree of confidentiality, while providing the reporting party with sufficient information for them to feel confident in the fairness of the process. Our view remains that reporting parties must receive an outcome to their complaint that enables them to understand the process that has been followed and have confidence in the fairness of decisions that have been reached. It is also essential to provide all parties with support for their welfare.

We have upheld or settled a higher proportion of complaints involving bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct than other complaints. These complaints are often complex, multi-faceted and providers may not be able to fully control events where outside agencies including the police or placement providers are involved. It can be challenging for providers to meet the expectations of all parties involved in these cases. It is important that providers give clear information to reporting and reported students about what the process can and can’t achieve. We welcome the new regulatory requirements coming into force in 2025 for providers on the OfS register about providing students with clear information and training staff.

In some cases, providers have not been able to demonstrate that they have undertaken a fair process due to failures in record keeping and in giving clear reasons for decisions.

A student on a professional healthcare course complained about the behaviour of other students on the same course in connection with a piece of group work. They said that they had received inappropriate messages from one member of the group, had been excluded from meetings about group work, locked out of critical documents and there had been disagreements about how to approach the work. The student initially asked for an apology from the rest of the group but didn’t want the matter to be formally recorded on the other students’ records. But the student then said that this was because they were worried about reprisals. On reflection, the student felt that the behaviour was a form of harassment connected to their disability, and that the other student’s behaviour ought to be considered under the provider’s fitness to practice regulations.

The provider investigated using the student complaint process. It decided not to use either the student disciplinary processes or the student fitness to practise processes. It concluded that there was evidence that the student had been excluded from discussions and locked out of key documents, but it did not see evidence that this was related to the student’s disability. It invited the student to speak to a member of staff with expertise in equality, diversity and inclusion and to submit a further complaint if they felt that they had experienced disability-related harassment. It asked the other students to write an apology. It encouraged those students to also write a reflective piece, but did not make this mandatory, taking account of the proximity of the students’ final assessments.

The student asked for the outcome of their complaint to be reconsidered. They were not satisfied with the apologies and felt that the provider’s actions were very lenient towards the other students and were not consistent with its stated “zero tolerance approach” towards bullying and harassment. The provider concluded that it had taken a reasonable approach. The student complained to us about the outcome and about how long the process had taken.

We decided to uphold part of the complaint (we decided in was Partly Justified).

We were satisfied that the provider had addressed the complaint in a timely way, taking just over the 90-day timeframe set out in our Good Practice Framework. But we did not think that the provider had clearly explained to the student why it did not consider the other students’ conduct under the formal disciplinary procedures. This was confusing in the light of its findings that the group had excluded the student. The provider said that it could not compel the other students to reflect on their behaviour or apologise because it had not made formal findings under the disciplinary processes, effectively leaving the student without a resolution to the complaint. It was also not appropriate to ask the student to make a new complaint about harassment when this related to the same behaviours that were the subject of a complaint that had not yet exhausted the provider’s processes.

We recommended that the provider provide refresher training for staff on the operation of its policy for addressing bullying. We also recommended that the provider pay the student compensation for the distress caused by its handling of the complaint.

A student beginning a healthcare course at an overseas campus was required to undertake an occupational health assessment. Shortly after the assessment, the student reported to the provider that they had been sexually assaulted by a medical professional employed by the occupational health firm. Around four months later, the student withdrew from the course and made a complaint about the way the provider responded to their disclosure.

The provider investigated the complaint and gave a formal response after five months. The student requested that this be reviewed. The provider took a further eight months to complete its review. It upheld several aspects of the student’s complaint. It accepted and apologised for unreasonable delays in its processes. It acknowledged that some communications from members of staff that were intended to convey that the provider was taking the situation seriously, were abrupt in tone. It accepted that the student found this hurtful. It also concluded that although staff had intended to be supportive towards the student, there was no evidence that they had provided specific advice about local specialist support services. The provider concluded that it had taken the actions it could to address the conduct of the medical professional, who was not one of its own employees. It had raised the issue at a senior level with the occupational health provider and ensured that the specific member of staff would not have any future interactions with its students. It also told the student how they could make a complaint directly to the occupational health firm. In its review, the provider decided that it could have given the student more information about what this process might look like or what it might achieve.

The provider apologised to the student for the issues identified and offered them £4,000 in compensation. The student was dissatisfied and complained to us. They said that the compensation did not reflect the severity of the impact of what had happened.

We acknowledged that the student had been severely impacted by their experience. But it was relevant to separate the impact of the assault itself from the impact of the provider’s actions after the student had reported what had happened. We concluded that the provider had undertaken a careful review, and was applying learning from the complaint, including considering whether it needed to amend its policies to be clearer about non-provider employees with whom students come into contact during their studies. The apology and offer of compensation were a reasonable response to the flaws it had acknowledged in responding to the student’s complaint. We did not uphold the student’s complaint (we decided it was Not Justified) on the basis that offer the provider had made was reasonable.

We will be continuing our focus on harassment and sexual misconduct in 2025, when we will consult on a new section of the Good Practice Framework.